Nitrogen is one of those good guy/bad guy deals. Nitrogen is a common and important element, and one of the building blocks of protein. Indeed, without it, your cattle would have a much harder time processing the rough forages they consume.

Plants take up nitrogen from soil in the form of nitrates — combinations of nitrogen and oxygen. On improved pastures, nitrogen fertilizer or manure can aid plant growth. And when everything is normal, very little nitrate accumulates in plants; stems and leaves rapidly convert the nitrate to plant amino acids and protein.

But nitrogen can play the bad guy as well. Under certain conditions, this conversion can be disrupted; the roots take up nitrate faster than the plant can change it to protein, and nitrate accumulates in the plant. Some types of plants, especially annuals, can accumulate high levels.

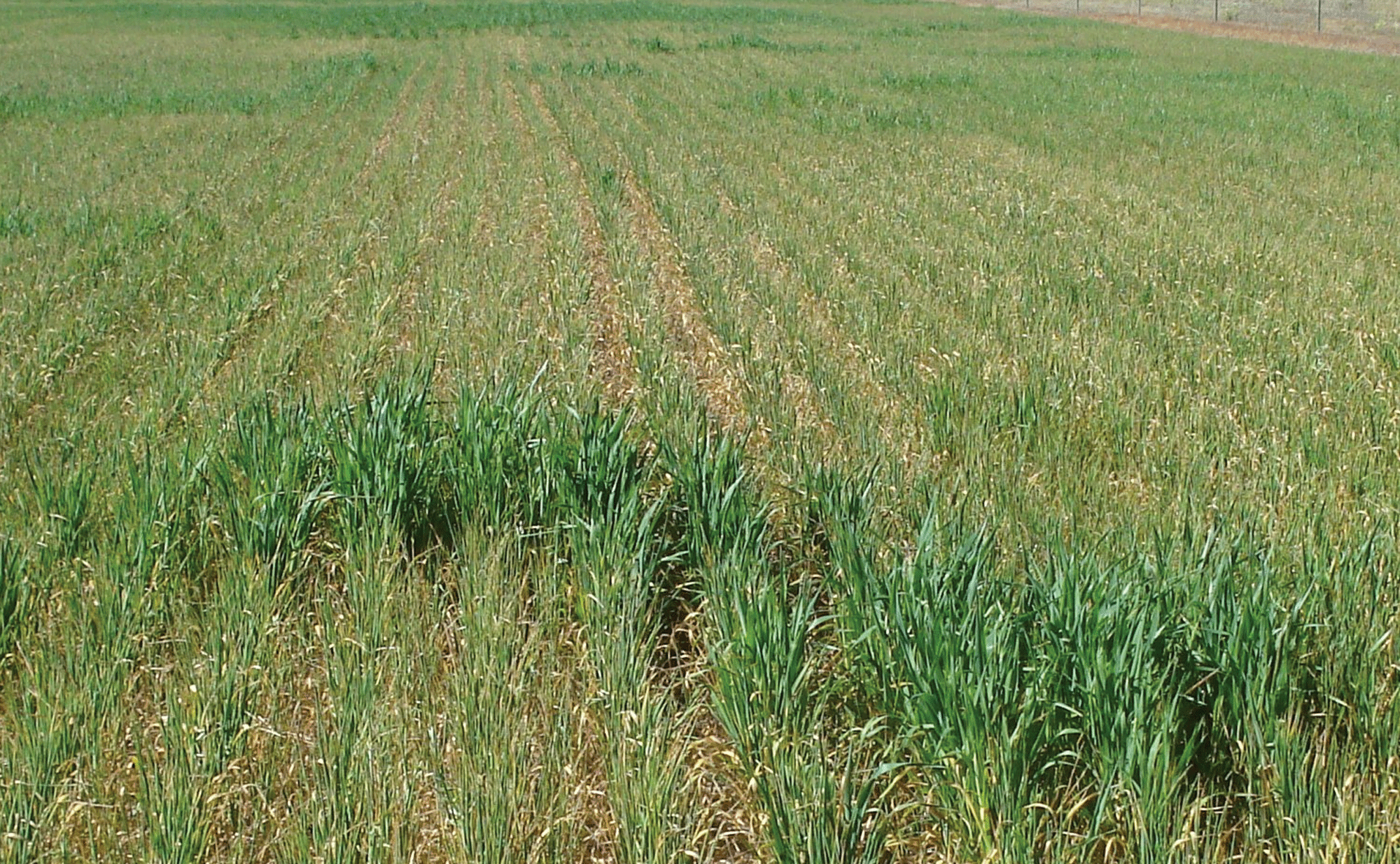

Drought stress is one situation that can cause plants to accumulate nitrates. Shannon Williams, Lemhi County Extension educator, Salmon, Idaho, says some types of crops — whether grazed or used as hay — should be checked for nitrate levels.

Nitrates and nitrites

Under normal conditions, nitrate ingested by ruminants is converted to nitrites by rumen bacteria, then changed into ammonia and then to bacterial protein, according to Ken Olson, Extension beef specialist, South Dakota State University. “The original form [nitrate] in the plant is not poisonous. It’s the nitrites that are toxic,” he says.

The problem is that in ruminant animals that consume forages high in nitrate, the nitrate is converted to nitrite faster than nitrite is converted to ammonia. If higher-than-normal amounts of nitrate are consumed, accumulation of nitrite may occur in the rumen and become toxic. This is why consuming plants with high nitrate levels is a bigger problem for ruminants than for horses, pigs or other animals with a simple stomach.

The amount on any one day may not be toxic, but it can eventually exceed the threshold for safety. “The first thing we notice in pregnant cattle or sheep is abortions,” Olson says. If the animals keep eating high-nitrate feed, continuing toxicity and accumulation leads to muscle tremors, weakness and death.

Excessive nitrite in the rumen is absorbed into the bloodstream, where it converts hemoglobin to methemoglobin — which is unable to transport oxygen. When an animal dies from nitrate poisoning, it is due to a lack of oxygen.

As long as the feed is below dangerous thresholds, nitrates are converted to nitrite in the rumen and the microbes continue the process of conversion, changing the nitrites to ammonia. “Rumen microbes can then use ammonia to form amino acids. This is how a ruminant synthesizes protein,” Olson explains.

The process in plant metabolism is similar to what occurs in the rumen. “The plant pulls nitrate from the soil to get nitrogen. In the plant, the nitrate is converted to nitrite, then to ammonia and then to amino acids and protein. The nitrate sometimes gets stuck there and never gets converted to ammonia — as when the plant is drought-stressed. It can’t finish the process,” he explains.

“Sometimes other things affect plant metabolism. During a cloudy, wet summer, there can also be nitrate problems in forage because photosynthesis slows down without adequate sunlight. There are many environmental stresses that can lead to high nitrates in plants — because they don’t get converted properly to plant protein,” Olson says.

“Even the time of day matters, regarding the best time to cut hay. It’s safest to wait until afternoon, because plants accumulate nitrates from the soil all night long, but there is no photosynthesis until daylight. Plants store nitrates until they can be processed, so levels are highest in the early morning and lower in the afternoon,” he says.

Herbicides can also increase nitrate levels, if the amount of herbicide is not enough to kill the plant but affects metabolism. Plant maturity makes a difference as well. Nitrate levels decline as plants mature.

Nitrates accumulated early in growth eventually get converted to protein. “If we delay cutting a small grain crop for hay until the plants are more mature and starting to form seed heads, levels will be lower,” Olson says.

Problem plants

Species that tend to accumulate higher nitrate levels include grains, sorghum, sudangrass, sorghum-sudan hybrids, corn, soybeans, fescue, pearl millet and bermudagrass.

“Sorghum and sudangrass may also contain prussic acid. If you are exploring options with summer annuals or cocktail mixes, look farther than just their grazing tolerance, how fast they grow, nutritional content, etc.” says Williams.

Brassicas like turnips and radishes can also accumulate nitrogen in drought conditions. “A person has to learn how to feed or graze a new forage without risk of nitrate poisoning,” she says.

“Crops damaged by frost or hail also have reduced photosynthetic capacity. The roots are usually unaffected and continue to supply the same amount of nitrogen, but the upper part of the plant is unable to use it efficiently, so the nitrate accumulates,” Williams says.

The nitrate-to-protein cycle in a plant is dependent on adequate water, sunlight and proper temperature for rapid chemical reactions. If any of these factors are inadequate (water, sunshine and warmth), the root continues to absorb nitrate, storing it unchanged in the stalk and leaves rather than converting it to protein.

Certain weeds can be nitrate accumulators. If they are grazed or baled in hay, they can cause problems. Wild oats, quackgrass, pigweed, lambsquarter, bull thistle, kochia, nightshade, Russian thistle, some of the mustards and many other weeds that we sometimes find in forage crops are nitrate accumulators.

“If they happen to contain a lot of nitrate, they can be deadly in hay. Barnyards and corrals may grow weeds, and if you put cattle in these areas — such as in the fall when working cattle — they may consume the weeds,” she says.

“If you are planting grain, there may be some weed seeds mixed in, or if it’s a new seeding on ground you haven’t torn up before, sometimes weeds come in. The seeds are very hardy and can last for years, waiting for an opportunity,” says Williams.

“Usually what causes excessive accumulation of nitrates is drought stress [lack of rain or shortage of irrigation water] or overfertilization with nitrogen.” Even a normal amount of fertilizer when plants don’t receive enough moisture to grow properly may result in too much nitrogen.

It’s important to test soils to see how much fertilizer you actually need. Accumulation of nitrate occurs when plant growth is less than half of normal, or when nitrogen application (fertilizer) is more than twice what is recommended.

Editor’s Note: This was part one of a two-part series. In part two, we’ll look at forage testing and how to feed questionable hay.

Smith Thomas is a rancher who writes from Salmon, Idaho.

Leave A Comment