By Tom Brink

During the past two decades, approximately 200,000 U.S. beef cow operations have exited the business—a decline of 22%, or slightly more than 1% per year. There are many reasons why this trend occurred, but the largest factor was financial pressure. Average and below average producers break even or lose money during most years. Many eventually choose to permanently leave the business.

This brings us to what might be called the curse of being average. Ranking in the middle or finding yourself at the “mean” is acceptable in numerous situations, but not in beef cattle production.

When my daughter, Erin, entered medical school some years ago, a professor wisely counseled her class not to be concerned if they found themselves in the middle of the bell curve for the first time in their lives. When the competition is stiff, average is OK. Many of us own pickups that are average for horsepower and towing capacity. That is acceptable, because most full-size trucks built in the past 10 years can adequately get work done, be it hauling a load of posts, pulling a gooseneck down the road or performing many other tasks.

However, we can’t say that average is good enough in the commercial cow-calf business. Being average is not going to work well here—there is no long-term profitability in it. Doing business as an average cow-calf operator is something to be avoided in every manner possible. In fact, being average will place the farm or ranch only a couple of bad years (or bad breaks) away from insolvency. All too often, average equals out of business.

Profiling average and better than average

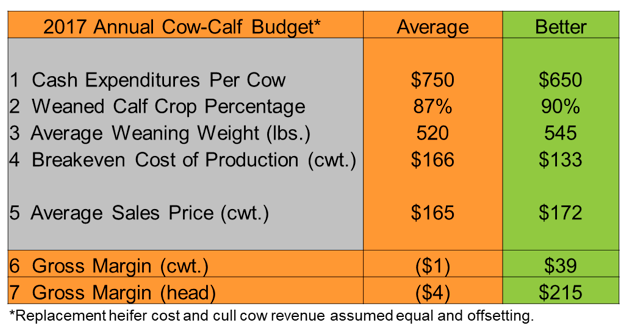

Consider Figure 1, which presents a simplified budget for a commercial cow-calf enterprise. There are four main production and cost variables that determine the financial outcome for every operation. These are annual expenditures per cow, weaned calf crop percentage, average weaning weight and average calf sales price.

The first three of these variables (lines 1-3) are combined to estimate the breakeven cost of production (line 4). Then we bring in the average sales price (line 5) to calculate gross profit margin (lines 6 and 7). To keep the math easy, annual revenue from cull cow sales are assumed to offset the cost of raising replacement heifers and therefore are not line item identified in the budget.

The column labeled “average” reflects the 2017 picture for an average cow-calf business. Despite calf prices remaining relatively high, being average last year produced little or no profit. Breaking even is all there was for an average cow-calf operation. The unit production costs were virtually equal to the sale price of the operation’s calves. Being average did not work out so well last year, and it probably won’t in 2018 either.

Contrast that situation to the “better” column in the table, which represents a better-than-average cow-calf herd. Costs per cow are below average, reproductive rates a few percentage points higher and weaning weights moderately heavier. Plus, this operation captures a higher calf sale price (despite heavier weights), due to producing premium, value-added calves combined with a superior marketing program.

Being better than average in several key categories resulted in a $215 gross profit per cow in this example, which is obviously a more desirable outcome. While the average producer broke even, the better producer had a positive year.

An above average performance requires attentiveness and commitment to many areas of the cow-calf enterprise. Cost control is important, but so is making sure cows have adequate nutrition all year long. The best producers are often those who find less expensive ways to accomplish the same tasks as their higher-spending counterparts.

Even so, three places not to scrimp on costs include (1) herd health, (2) genetics and (3) pasture management. Additionally, marketing must be a year-round effort. Good marketing starts with an understanding of what the market will pay a premium for. The next step is aligning your calf crop to fit those premium-oriented markets. Genetics and management play important roles.

Much of having strong financial results goes back to the cow. She must be a versatile female that favorably contributes on both the input and output sides of the enterprise. She must maintain herself without a lot of extra feed and breed back year after year, while still providing beneficial genetics that help the calf crop sell at the top of the market.

Likewise, bulls should be selected for the replacement heifers they can sire (in most cases) and to produce heavy, highly-marketable steers. As a producer, it is worth your time to seriously answer the question: In what aspect of the cow-calf enterprise is my operation better than average?

Lower cow carrying costs? Better fertility? Heavier sale weights? Higher calf prices? Maybe two or three of these accurately describe your operation. If so, you have avoided the curse of being average and are likely to remain profitable even when beef supplies are large, and the cattle market is less than accommodating.

Brink is CEO of the Red Angus Association of America.

Leave A Comment