It’s always wise to test any forage that has the potential to contain high nitrate levels. Conditions leading to nitrate accumulation can change from year to year with the same crop from the same field.

“Just because you didn’t have a problem one year doesn’t mean you won’t have a problem the next year,” says Shannon Williams, Lemhi County Extension educator, Salmon, Idaho. “There might be different growing conditions, or even different management.”

It’s much cheaper to pay $25 to get the forage tested than to lose even one animal — or have to treat some of them. “If nitrate poisoning is severe, you won’t have a chance to treat the animals; you just find them dead, or you may see a lot of abortions if the cows were pregnant,” says Williams.

Forage samples can be sent to a lab for testing before you feed that forage, or before you let cattle into that pasture to graze. Results can be received within a week or so. Because soil fertility can vary across a field, it is important to sample forage at several locations, or take hay samples from several bales.

Forage samples can be sent to a lab for testing before you feed that forage, or before you let cattle into that pasture to graze. Results can be received within a week or so. Because soil fertility can vary across a field, it is important to sample forage at several locations, or take hay samples from several bales.

“Some Extension offices can do a quick test without having to send it to a lab. If a producer brings me a feed sample, I can test it with a solution that contains sulfuric acid and some other ingredients that react with the nitrates. For this test, we cut the stems open and apply a few drops of solution. I usually include stems, leaves, seed heads, etc., so I have a representative sample,” Williams says.

“If it turns blue, we know there are nitrates. We don’t know if it’s just a little or a lot, but this tells us whether nitrates are present or absent. If it doesn’t turn blue, we can tell the producer it’s safe to graze or cut for hay. I’ve done enough of these tests to know that the quicker it turns blue, and the deeper the blue color, the higher the nitrate level. In that situation, I encourage people to send in a sample,” she explains.

The quick test can give an idea if the feed is safe much more quickly than waiting for the results of a lab test. “But if there are nitrates, you need a lab test to know the actual level, to guide you in feeding management. You’d know if you can safely feed it to any cattle [very low level], or just non-pregnant animals. At a certain level, you could still get by if you mix it with another forage that has no nitrates. A high level, however, would not be safe to feed under any conditions. Knowing the nitrate level enables you to make a management decision,” says Williams.

Make sure the lab will send back a scale for feeding recommendations as well as the nitrate level. “Not all labs measure or test the same way; their scale may be different. Your Extension educator can help you interpret the scale. We always send samples to the same lab, so we are familiar with their measurement rates,” says Williams.

“It’s important to plan ahead. Often I get samples brought to me that contain nitrates, and I ask the rancher how soon he plans to put cows in that pasture, or cut this field as hay. If he already did, or plans to do it tomorrow, that puts him in a risky situation, Williams says.

To be safe, allow 10 days from the time the sample is mailed to the lab. ‘We often get the results back quicker, but this gives some leeway. Actual time will depend on how busy the lab is and how long the mail takes. If you usually cut oat hay on a certain date, write a reminder on the calendar well ahead of that date — to test the hay before you cut it,” she says.

When purchasing cereal hay, such as oats, barley, wheat or straw to use in conjunction with a protein supplement or alfalfa, it always pays to have it tested first — or ask if the hay grower had it tested. “If it’s been tested, ask for a copy of the test results to know how best to feed it. You might be willing to pay more for hay or straw that’s already been tested because you don’t have to wait a week or so for the results,” says Williams.

Feeding questionable hay

The only way to safely feed high-nitrate forage is to blend it with other feeds to dilute the nitrates. This is easy with a bale processor. It’s more challenging if you’re feeding round bales in a bale feeder or unrolling them on the ground. One option is to roll out the hot hay, then roll some safe hay on top.

“Hay with a low level of nitrates can be safely fed to non-pregnant animals, such as bulls or yearlings, or mixed with other hay before you feed it to pregnant cows,” Williams explains. The only way to safely feed high-nitrate forage is to blend it with other feeds to dilute the nitrates.

Some producers put high-nitrate hay into a total mixed ration. If they know the levels, they can blend it with a grass mix to bring nitrate levels down. Test your other feeds so you can accurately determine how to blend them and adequately dilute the nitrates.

“If you do have to mix with other hay, the next question is how to do it, especially big round or big square bales that you’d typically just put in a feeder or roll out [or flake off the feed truck] in the field,” says Williams. “Most of the nitrate poisonings I’m aware of or heard about occurred in the most aggressive boss cows that come first when you roll it out, or keep other cows away from the feeder. Aggressive cows get more of it and end up with poisoning,” she explains.

“Some producers might fence cattle away from the feed area and roll safe hay on top of the other, to mix it — so the cows have to eat down through the safe hay to get to the ‘hot’ hay — and then turn the cows in after it’s been rolled out. It’s easier to mix when feeding small bales,” says Williams. If a person uses a bale processor for big round bales, two types of hay can be mixed.

Signs of nitrate poisoning

Abortions in pregnant cows might be the first sign. “At a higher dose, cattle show signs of oxygen shortage, because nitrates take up the oxygen,” says Williams.

Signs of acute nitrate poisoning include labored breathing, muscle tremors, staggering gait and weakness. These animals generally have blue mucous membranes due to lack of oxygen in the tissues, fast breathing, high pulse rate, uneasiness, excessive salivation, frequent urination, and dilated and bloodshot eyes.

“If nitrate poisoning is suspected, call a veterinarian immediately to make a tentative diagnosis and start treatment,” Williams says. Affected cattle may die quickly unless treatment is given immediately. An injection of 1% solution of methylene blue (4 mg per pound of body weight) into the bloodstream can help.

If more than one animal in a herd is showing suspicious signs, you should suspect the feed. “Your vet can pull a blood sample to confirm the diagnosis,” Williams says.

Chronic nitrate toxicity may occur when animals eat a lower level of nitrates daily, over an extended period of time. “Signs in this situation might be more subtle and include lower weight gain, lower milk production, poor appetite, greater susceptibility to infections, etc. Chronic nitrate poisoning can cause abortions within the first 100 days of pregnancy. Reproductive problems may also occur, due to a nitrate or nitrite-induced hormone imbalance, and this might not be recognized as feed-related,” she says.

“Cows affected by nitrate poisoning during the last three months’ gestation may calve a few weeks prematurely. Most of these calves appear normal but die within 18 to 24 hours. Calves that survive — that were affected by nitrate poisoning — may have convulsions or seizures,” says Williams.

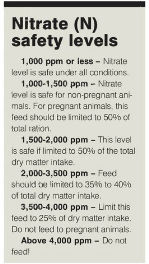

Nitrate (N) safety levels

1,000 ppm or less – Nitrate level is safe under all conditions.

1,000-1,500 ppm – Nitrate level is safe for non-pregnant animals. For pregnant animals, this feed should be limited to 50% of total ration.

1,500-2,000 ppm – This level is safe if limited to 50% of the total dry matter intake.

2,000-3,500 ppm – Feed should be limited to 35% to 40% of total dry matter intake.

3,500-4,000 ppm – Limit this feed to 25% of dry matter intake. Do not feed to pregnant animals.

Above 4,000 ppm – Do not feed!

Smith Thomas is a rancher who writes from Salmon, Idaho.

Leave A Comment