Growing up, my grandfather would tell me “remember, you’re in charge,” every time I would pull away with a load of calves or on a tractor heading for the fields. My safety was his primary concern, as well as the well-being of his equipment and livestock. However, there were deeper messages in his words: pay attention, think for yourself and be responsible for your actions. Every choice has a consequence, good or bad. Working in agriculture is an inherently dangerous profession, and safety must be a priority for every producer. Using proper animal handling and stockmanship principles, along with a little common sense, can keep stress and incident levels to a minimum. This is especially true when loading, transporting and unloading livestock.

The biological impact of stress in cattle is a complex interaction of stimuli and the endocrine system of the animal. A review of scientific literature shows cattle that are handled poorly prior to transport, loaded incorrectly or mishandled after unloading are more likely to become ill, have greater shrink and exercise decreased performance post-transport. Improper handling during transport can also have negative carcass impacts, such as bruising or dark-cutters, decreasing that animal’s value at harvest.

In my experience, with ranchers and professional transporters alike, the goal when shipping cattle is “get them on the truck and down the road.” Working in a timely fashion is absolutely important, but some precautions and planning should be taken before, during and after the cattle arrive at their destination.

Get to your destination quickly and safely:

Know your route and plan for any impediments. Try to avoid unnecessary stops and drive responsibly, respecting your cargo as well as other motorists on the road. Be mindful of the trip duration, time of day and weather conditions the cattle will experience while in transit. The less time livestock have to spend on the road, the better.

Treat them like your own:

Care for the animals like they are your own, regardless if a bill of laden has been signed. In some instances, the majority source of a producer’s annual income is riding in your trailer. They are entrusting you and your abilities to safely deliver their livestock to market in a safe and efficient manner. Do not assume that responsibility carelessly or lightly.

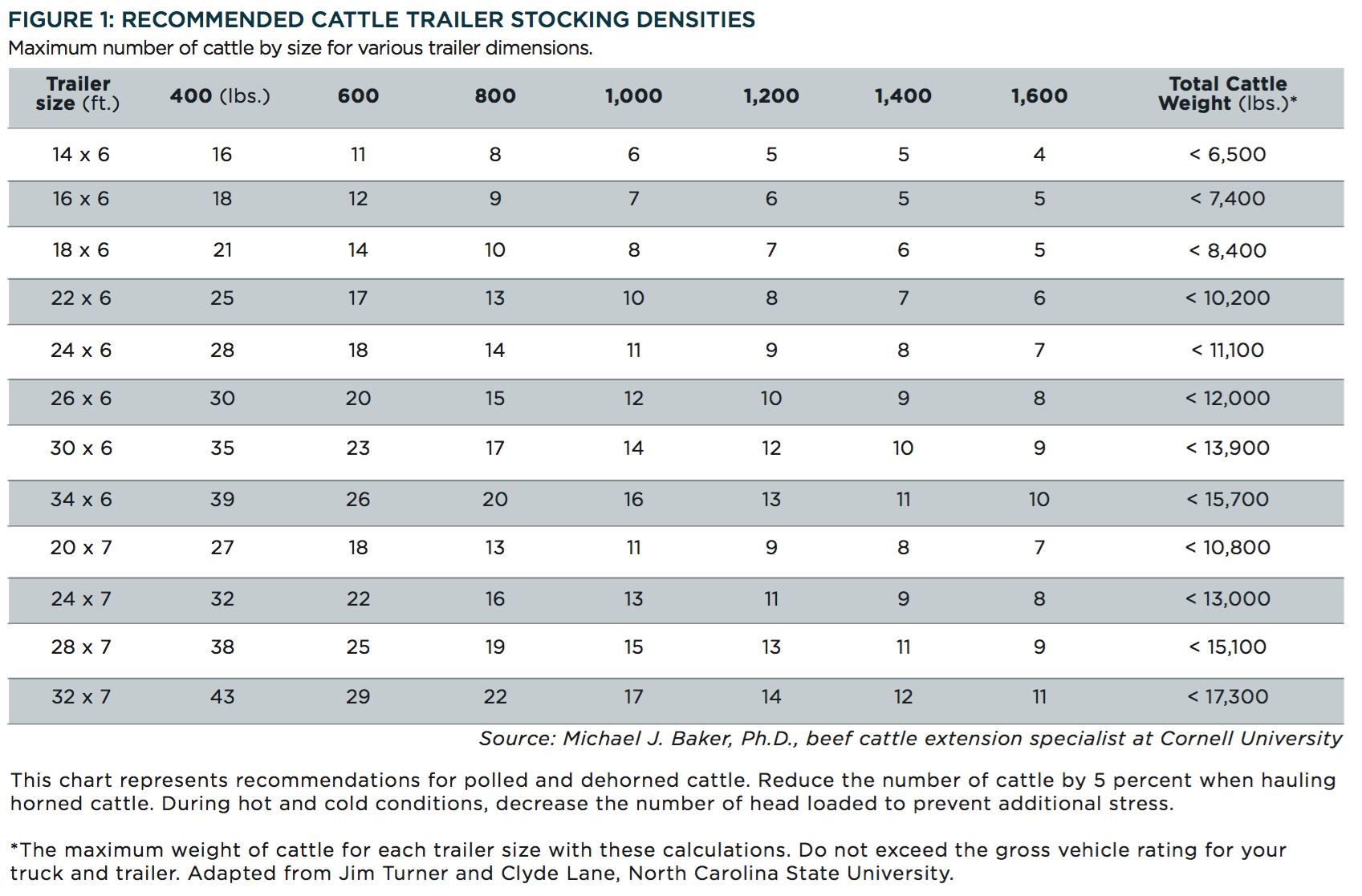

Trailer space and load density:

Just because they can fit doesn’t mean they should. Overloading a trailer is not only dangerous to the safety and well-being of the cattle, but it can be hazardous for the driver if he or she is not able to safely stop or control their vehicle due to improper load distribution or exceeding the capability of their trailer and/or truck. Utilize cut-gates so animals have the space they require but also remain secure so they cannot harm one another due to over- or under-loading.

Check your gates, then check again:

If you’re not sure, go look for yourself. The last thing anyone wants to do is chase after cattle that escape the pens or loading facility because a gate was not securely closed.

Remember, you do not have a static load:

Cattle move and shift in a trailer, and their movement affects your vehicle and how it operates going down the road. Make gradual stops and turns, as well as smooth and steady starts to help the cattle maintain their balance and footing. Animals that slip and fall can become injured or lame, a situation that no livestock producer wants to encounter.

The Transportation Quality Assurance Program offered by the national Beef Quality Assurance (BQA) program is an invaluable resource for anyone who hauls livestock, no matter your skill level or trailer size. The ability to efficiently and effectively move cattle from location to location is important to minimize stress, reduce shrink and ensure cattle can perform at their best after they walk off your trailer. You are in charge, and it is your responsibility that you and your cargo safely arrive at your destination.

Source: Noble Research Institute

Leave A Comment