If you want to have a conversation with Fred Borman about his cows, don’t do it in his pickup driving around looking at his cows. He spends way too much time being part of the radio chatter that goes on between the cowboys and his general manager, Brent Morrison.

But that’s just fine with Fred. Although the ranch, farm and backgrounding feedlot he owns along with his father, famed Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman, are spread out over four deeded operations and two leased ranches, Circle B LLC is a tightly run and close-knit operation.

All of the 13 employees spread across the operation know they can talk to Fred or Brent about anything, at any time — from work-related issues to how the kids are doing in school. “It’s a good family place,” Morrison says of the Circle B, headquartered up Tullock Creek near Bighorn, Mont. “At least that’s what Fred and I try to do.”

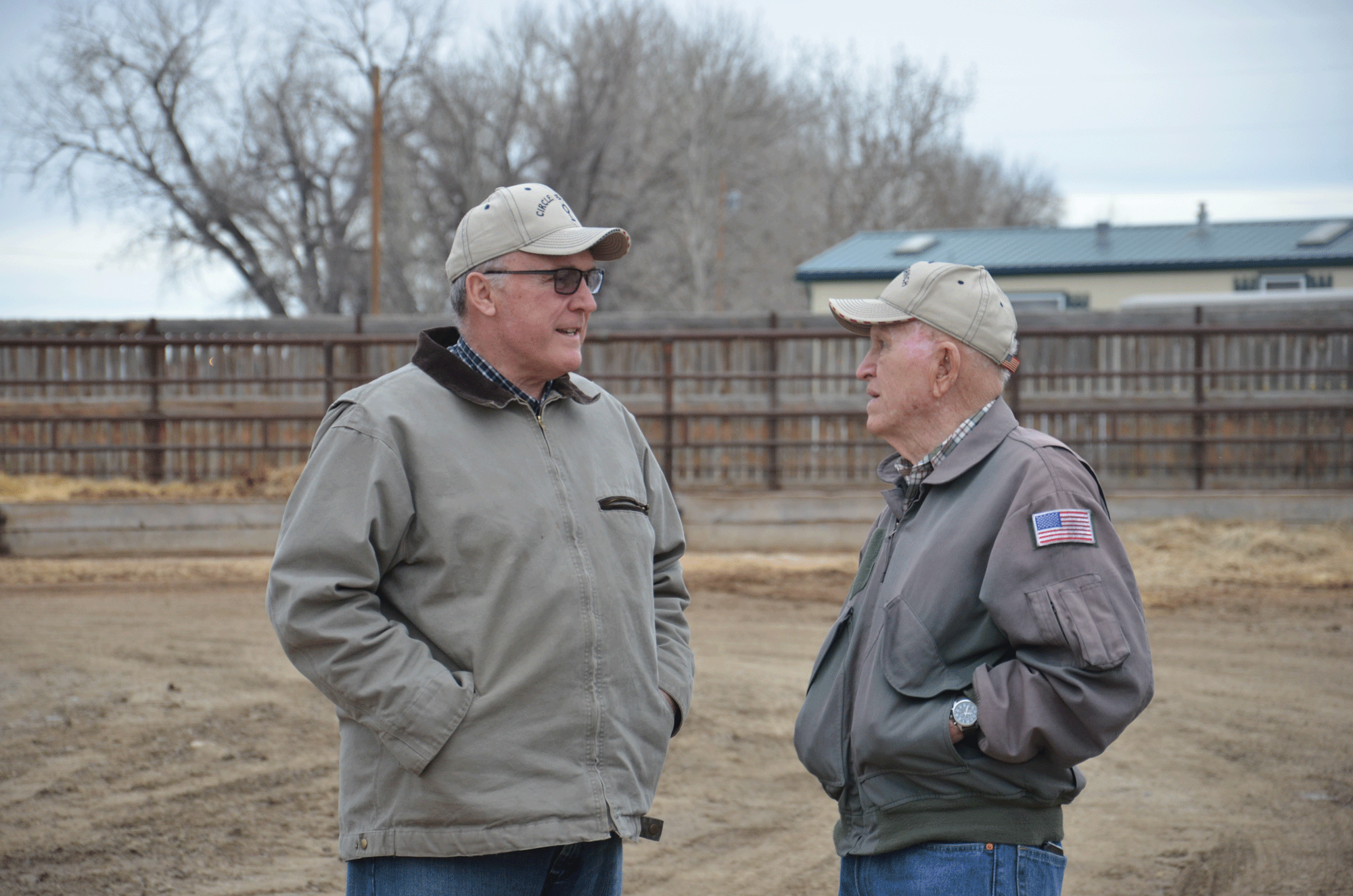

Fred Borman (left) discusses the results of the weigh-up with his father, Frank, the famed Apollo 8 astronaut.

It’s also a good family place if you’re a cow. Borman and Morrison work very hard to make sure of that, too. Dig a little deeper into both subjects, and you’ll find they are convinced the two are closely connected. Creating a family-friendly workplace for the employees makes for a more productive cow herd.

“The key to this whole deal is to have a quality product and really great people. And we’re lucky to have both,” Borman says. “The F1 calf is a great cross, and we’ve got a great crew of people that work for us and a great group of people that work with us. It’s those relationships that make this work.”

The F1 calf that Borman speaks highly of is a Black Baldy. The Circle B is a terminal cross operation, running Hereford bulls on Angus cows. All told, they run around 3,200 cows and somewhere around 375 replacement heifers spread between the ranches, and farm around 1,200 acres of alfalfa and corn, all of which is used as feed.

Given that it’s a terminal operation, Borman focuses on numbers. “We run this ranch to make a profit,” he states.

And how does he do that? The goal year in and year out is 100% breed-up, 100% calf crop and 100% weaning percentage. They don’t always hit those numbers, but they consistently run only 1% to 2% below their goal.

Given that Borman ranches in southeastern Montana — not the easiest climate to winter a cow — that is a remarkable accomplishment.

How it’s done

There are multiple, interrelated management tactics that Borman and Morrison implement to accomplish those goals. They buy all their replacement heifers and breed them naturally in their backgrounding yard for one cycle, then on pasture for another cycle and pull the bulls after 60 days. They buy all their bulls from one seedstock operation. The heifer breeding season starts the first of June, and “we’ll have 75% bred the first cycle,” Borman says.

After the heifers leave the feedyard, it’s the cows’ turn. Bulls are turned out with the cows beginning in July. When breeding season is over, the cows and heifers graze on creek bottom pastures until everything is calved out — and enough groceries have grown in the pines so it’s safe to move them into the hills. A pregnant cow without enough to eat will nibble on pine needles, and that’s a sure way to get into an abortion wreck, Borman says.

While breeding with one bull per 20 cows goes a long way toward the ranch goal of 100% breed-up, come calving time is when hoofbeats really hit the ground. The cows calve on pasture and generally are problem-free, Morrison says.

But the heifers? That’s where very intensive effort is applied. “We probably work at calving differently than most guys do,” Borman says. “But our goal is to save every calf we can.”

And they do. “We take pride in what we’re doing, and we’re really fortunate to have the good group of guys that put the extra time into it,” Morrison says. The heifers run in a bottomland pasture near the calving pens and then are brought into the pens at night.

“We ride through them with a horse and a flashlight at night — take shifts,” he says. “One guy goes until midnight, the other goes from midnight on.” Using a whiteboard in the calving shed, the cowboys know what happened the previous shift and what to watch for during their turn.

Each ranch has a barn with calving jugs and a chute, should a difficult birth occur or a calf be born in a storm. But if all possible, Morrison says, they let the heifers calve outside. “If we think the calf can make it, if it gets up and sucks right away, we leave them out and let the heifers be heifers.”

Nutrition and health

“You have to spend money to make money in this business,” observes Scotty Anderson, with Prewitt and Co., the marketing representative for Circle B. “If you want to cut corners, you’re going to have results that show you cut corners. This is an outfit that doesn’t cut corners.”

That shows in the ranch’s health and nutrition programs, the first two legs in the Circle B’s profit equation. “You’ve got to have a healthy cow that’s on a good mineral program and on a good vaccination program,” Borman says. And a good parasite program as well. “Worming is the best return on a cow-calf man’s investment,” Anderson adds.

That philosophy extends to the calves, which are moved to the backgrounding feedlot after weaning. First, because their mamas are well-cared-for, calves get a strong shot of colostrum when they’re born and ample milk to go along with summer grass. What’s more, miles and miles of pipelines ensure that every pasture has fresh water year-round.

“We vaccinate them when we brand, we vaccinate them when we wean and we booster them two weeks later — and we ride pens like mad” after the calves are weaned and sent to the backgrounding feedlot, Borman says.

“And the end result is, when we get 3,500 calves in the feedlot and only lose 16, that tells me we’ve got a good mineral and vaccine program.”

Feed ’em right

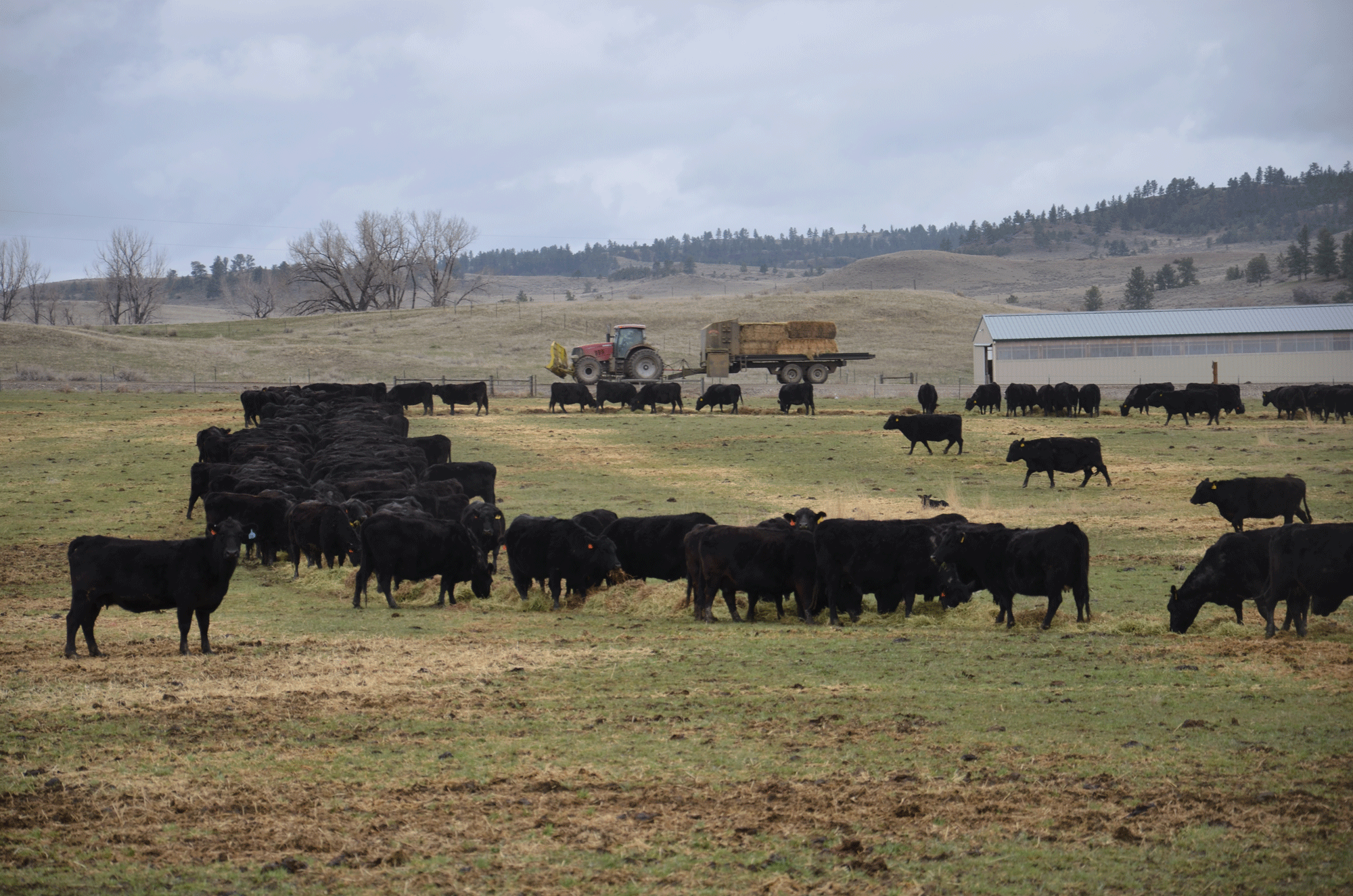

The chow line on the Circle B is a fine place to be if you’re a cow. The cow herd is fed a 50-50 mixture of alfalfa and barley straw, which provides ample energy and protein to keep the cattle from losing body condition in the tough Montana winters.

The companion piece to a sound health program is nutrition. That’s where the Circle B takes a hard turn from current conventional wisdom. Many ranchers will winter their cows on stockpiled pasture, scrimp on the supplement and be happy with an 80% weaning percentage.

Borman maintains that a strong nutrition program has better payback, both at calving time and when the calves are marketed. For 2017, the Circle B missed its goal of 100%, but not by much — it recorded a 98% calving percentage and a 98% weaning percentage.

The ranch’s 1,200 acres of farmland produces most of the feed for the operation. The corn is cut for silage and is used in the backgrounding ration. The alfalfa is baled in large squares and becomes winter feed for the cows, fed by an Easy Ration bale wagon.

“It’s got a live bottom, and it feeds straight into the beaters and spits out a big windrow,” Borman says. “In the wintertime, we put six barley straw bales on one side and six alfalfa bales on the other. Barley straw is about 4% protein, the alfalfa is 18% to 20% — so it comes out right at 12% protein.” In addition to ample protein, the mix also has plenty of energy.

The straw comes from a neighbor who grows barley for Coors. The cows are fed 28 to 30 pounds a day of the alfalfa-straw mixture, and they maintain body condition throughout the winter and are in better-than-adequate condition come calving time. On the Circle B, adequate just isn’t good enough.

Marketing advantages

That same philosophy applies to the third leg of the Circle B’s profit equation — marketing. In the early years, Circle B calves were sold on Superior’s Country Page over the internet and then on video. This worked very well, as the calves and the ranch grew in reputation.

But Borman and Anderson, in spite of very successful sales with Superior, knew there were additional premiums they could capture. But selling calves in 2013, ’14 and early in ’15 didn’t take much effort. “If they had a heartbeat, they rang a bell,” Borman says, and there was no advantage to producing program cattle.

But things change — and when Borman and Morrison sat down with Anderson and the rest of the Prewitt group to discuss marketing their 2016 calves, the Prewitt group suggested selling the calves as NHTC — non-hormone-treated cattle.

And, as Borman is apt to say, they rang a bell. The standard program for Circle B calves is to go to the feedlot in September and October after weaning, where they’re fed a ration of alfalfa, silage, earlage and supplement. Last year’s calves came in to the backgrounding yard averaging 535 pounds in fall 2016. During the wintertime cold, they were bedded on barley straw, which Morrison says adds a quarter-pound of gain a day.

Borman sold the heavy end in February 2017, weighing between 850 and 950 pounds — for a nickel premium over the market price. The light end hit the road at the end of March at roughly the same weight and for the same premium. To say Borman was pleased would be an understatement.

Pleased but not satisfied, however, because there are more premiums for the taking. For their 2017 calf crop, the Circle B calves will be part of Whole Foods’ Global Animal Partnership (GAP) program, which Anderson says will pay an additional nickel above that paid for NHTC cattle.

That’s not to say it’s easy money to get. GAP is an intensive five-step program that covers a wide swath of how a rancher runs the operation, beyond just the cattle. Circle B passed the audit for the GAP program and has qualified for Step 1. Given Borman’s management philosophy, that’s no surprise.

Does pouring all those inputs into his cattle pay him back? His short answer is yes. “Plus, we think it’s the right thing to do for our animals. We do everything we can to take care of our product.”

He has no argument with ranchers who take a different management approach. “I’m not saying my way is right, and their way is wrong. I’m just saying this is what we’re comfortable with. [The cattle] are our biggest investment. I’ve got probably $10 million in cows, calves and bulls. Why would I not take care of them?”

Leave A Comment